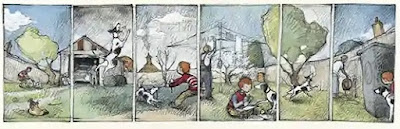

Freya Blackwood has been illustrating children’s book for some years now, and I have always been charmed by the characters that she creates, and by the way in which she lays out the pages. The panel above, for example , tells the story in such a creative and unique way. I have studied her work myself to learn more about picture book art direction.

Here is an interview that Freya recently gave in which she describes her creative process. Below is a review of one of her books.

For ages 3 to 5

Little Hare Books, 2017, 978-1760128982

One day Maudie decides that she needs some exercise and Bear agrees that some fresh air “would be nice.” Maudie then suggests that they go for a bike ride and Bear readily agrees.

Before they can leave the house Maudie is going to need to find her sunglasses. Then she needs their hats, which takes time to sort out because there are lots of hats to choose from. Next, Maudie gets a scarf.

Each time Maudie goes off to get something Bear patiently waits for her. He understands how it is when a little girl needs to prepare for an outing. Bear is clearly a very good friend.

Children and their grownups alike will be charmed by this delightful little book. With its whimsical illustrations, its charming characters, its clever story, and its funny ending, this book shows to great effect how a simple story can be a rich one.

Little Hare Books, 2017, 978-1760128982

One day Maudie decides that she needs some exercise and Bear agrees that some fresh air “would be nice.” Maudie then suggests that they go for a bike ride and Bear readily agrees.

Before they can leave the house Maudie is going to need to find her sunglasses. Then she needs their hats, which takes time to sort out because there are lots of hats to choose from. Next, Maudie gets a scarf.

Each time Maudie goes off to get something Bear patiently waits for her. He understands how it is when a little girl needs to prepare for an outing. Bear is clearly a very good friend.

Children and their grownups alike will be charmed by this delightful little book. With its whimsical illustrations, its charming characters, its clever story, and its funny ending, this book shows to great effect how a simple story can be a rich one.

|

| Artwork from Freya’s book Harry and Hopper, which won the Kate Greenaway award in 2010. |