Welcome!

Tuesday, April 5, 2022

Happy Birthday, Richard Peck, author extraordinaire.

Monday, April 4, 2022

Jane Goodall - Scientist, Environmentalist, Writer, and Reader

|

| Illustration by Petra Braun |

When I was a student at the University of Oxford studying zoology, Jane Goodall, the famous primatologist, came to town to sign her latest book at Blackwells, Oxford's most marvelous bookshop. Naturally I went to the signing, and as the line was not too long I was able to have a short talk with Dr. Goodall. She was a very slender, almost fragile, looking lady with a soft voice. She looked at me with her penetrating eyes as I stumbled over my words, blushing furiously "Take a breath," she said smiling and tilting her head slightly to one side. Her words made me laugh, and after that I was able to tell her how the books she, Gerald Durrell, and David Attenborough had written had set me on my current path.

Friday, April 1, 2022

Happy Poetry Month - A review of Classic Poetry

Tuesday, March 29, 2022

Please look after this bear.

In the late 1930s-1940s, Michael Bond, author of Paddington Bear, saw Jewish refugee children (Kindertransport children) walking through London's Reading Station, arriving in Britain escaping from the Nazi horrors of Europe.

Mr. Bond, touched by what he saw, recalled those memories 20 years later when he began his story of Paddington Bear. One morning in 1958, he was searching for writing inspiration and simply wrote the words: “Mr. and Mrs. Brown first met Paddington on a railway platform…”

“They all had a label round their neck with their name and address on and a little case or package containing all their treasured possessions,” Bond said in an interview with The Telegraph before his death in 2017. “So Paddington, in a sense, was a refugee, and I do think that there’s no sadder sight than refugees.”

Paddington Bear - known for his blue overcoat, bright red hat, and wearing a simple hand-written tag that says “Please look after this bear. Thank you,” Paddington embodies the appearance of many refugee children. His suitcase is an emblem of his own refugee status.

“We took in some Jewish children who often sat in front of the fire every evening, quietly crying because they had no idea what had happened to their parents, and neither did we at the time. It’s the reason why Paddington arrived with the label around his neck”.

Michael Bond died in 2017 aged 91. The epitaph on his gravestone reads "Please look after this bear. Thank you."

Please look after all the young Bears from all around the world who are having to flee conflict and war.

Shared from @DavidLundin

Friday, March 25, 2022

Books for Refugee Children

Winter is melting into spring - With a beautiful picture book by Kazuo Iwamura

Tuesday, March 22, 2022

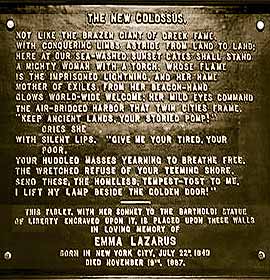

Women's History Month - Emma Lazarus, an activist and author of poetry and prose.

Illustrated by Clair A. Nivola

Nonfiction Poetry Picture Book

For ages 5 to 7

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2013, 978-0544105089

When Emma was little she had a very comfortable life living in a lovely, large home with her mother, father, and siblings. She lacked for nothing, and was able to indulge in her love of books. She had the time to read, and spent many hours writing stories and poems. The people she spent time with came from similarly comfortable backgrounds, and the world of New York’s well-to- do people was the only one she knew.

Then one day Emma visited Ward’s Island in New York Harbor and there she met immigrants who had travelled across the Atlantic as steerage passengers. They were poor and hungry, and many of them were sick. They had so little and had suffered so much. Like Emma, they were Jews, but unlike her they had been persecuted and driven from their homes. Friends and family members had died, and now here they were in a strange land with no one to assist them.

Emma was so moved by the plight of the immigrants that she did her best to help them. She taught them English, helped them to get training so that they could get jobs, and she wrote about the problems that such immigrants faced. Women from her background were not supposed to spend time with the poor, and they certainly did not write about them in newspapers, but Emma did.

Then Emma was invited to write a poem that would be part of a poetry collection. The hope was that the sale of the collection would pay for the pedestal that would one day serve as the base for a new statue that France was giving to America as a gift. The statue was going to be placed in New York Harbor and Emma knew that immigrants, thousands of them, would see the statue of the lady when their ships sailed into the harbor. What would the statue say to the immigrants if she was a real woman? What would she feel if she could see them “arriving hungry and in rags?” In her poem, Emma gave the statue a voice, a voice that welcomed all immigrants to America’s shores.

In this wonderfully written nonfiction picture book the author uses free verse to tell the story of Emma Lazarus and the poem that she wrote. The poem was inscribed on a bronze plaque that is on the wall in the entryway to the Statue of Liberty’s pedestal. It has been memorized by thousands of people over the years, and has come to represent something that many Americans hold dear.

At the back of the book readers will find further information about Emma Lazarus and her work. A copy of her famous poem can also be found there.

|

| The plaque inside the statue of liberty |

Sunday, March 20, 2022

Happy Spring! With a review of Crinkle, Crackle, Crack It's Spring.

Saturday, March 19, 2022

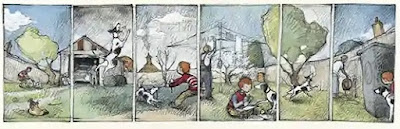

Getting to know Freya Blackwood, author and illustrator

Little Hare Books, 2017, 978-1760128982

One day Maudie decides that she needs some exercise and Bear agrees that some fresh air “would be nice.” Maudie then suggests that they go for a bike ride and Bear readily agrees.

Before they can leave the house Maudie is going to need to find her sunglasses. Then she needs their hats, which takes time to sort out because there are lots of hats to choose from. Next, Maudie gets a scarf.

Each time Maudie goes off to get something Bear patiently waits for her. He understands how it is when a little girl needs to prepare for an outing. Bear is clearly a very good friend.

Children and their grownups alike will be charmed by this delightful little book. With its whimsical illustrations, its charming characters, its clever story, and its funny ending, this book shows to great effect how a simple story can be a rich one.

|

| Artwork from Freya’s book Harry and Hopper, which won the Kate Greenaway award in 2010. |

Thursday, March 17, 2022

Happy Birthday, Kate Greenaway

|

| Art from the Pied Piper of Hamelin |

Kate Greenaway was the most popular children’s book illustrator of her generation. During the last two decades of the 19th century, her idyllic illustrations presented an aspirational view of childhood that charmed readers in her native Britain, Europe, and as far away as America. Like her peers Walter Crane and Randolph Caldecott, she collaborated with London’s best color-printer to produce a new, innovative product—high-quality books for the juvenile market. What set Greenaway apart in this triumvirate of excellence was her unique vision. While Crane and Caldecott illustrated stories written for children, Greenaway’s work featured the children themselves—quaintly dressed in ruffles and bonnets and set against picturesque, bucolic landscapes.

|

| Kate Greenaway in her studio in 1895 |

The enchanted quality of Greenaway’s illustrations reflected her own memorable childhood. She was born in London into a lively, creative family. Her father was a skilled engraver and her mother an inventive milliner. Kate was an imaginative child who absorbed the beauty of the countryside and the intrigue of city life with equal admiration. “Living in that childish wonder is a most beautiful feeling,” she once confided to a friend. “I can so well remember it. There was always something more—behind and above everything—to me; the golden spectacles were very, very big.” Through those golden lenses, Greenaway observed her father’s engaging business. John Greenaway kept a scrapbook of engraving examples, and Kate remembered how a Cruikshank illustration of an execution fascinated and horrified her. Providing an antidote were the half penny fairytales in the family library. Bluebeard and Beauty and the Beast were among her favorites—mysterious, terrifying tales that nonetheless, ended well.

Both parents encouraged Greenaway’s interest in art, and by the time she was twelve, she was winning prizes at a local academy. As her skill increased, she attended London’s South Kensington School and then Heatherley’s, the first British art school to admit women to life-drawing classes. By the age of 21 she was enrolled in London’s newly formed Slade School, an institution dedicated to equal education for women. While still attending classes, Greenaway developed her distinctive style, creating watercolors of children dressed in clothing she designed, assembled and fitted on models or lay figures. Although her costumes resembled the styles of the Regency era, a half-century earlier, they owed as much to invention as to authenticity. When Greenaway finished her education, her drawings found a modest market in the lesser-known periodicals.

A turning point in Kate Greenaway’s career came when a Valentine she designed sold more than 25,000 copies. Her share of the profits was less than three pounds, but the card’s popularity yielded years of work designing birthday and holiday greetings. Although the enterprise provided a modest income, Greenaway’s cards were either unsigned or initialed. Her biographer, M. H. Spielmann, noted that at the age of 33 she was still “the hidden mainspring of a clock with the maker’s name upon the dial.” Greenaway’s fortunes changed in 1878 when she presented a portfolio of 50 drawings with accompanying verses to printer, Edmund Evans. Years later, Evans recalled that first meeting, “I was fascinated with the originality of the drawings and the ideas of the verse, so I at once purchased them and determined to reproduce them in a little volume.” Edmund Evans engraved and printed Greenaway’s “little volume” in 1879. Although the publisher questioned the wisdom of investing in an unknown artist, Evans was in the position to take a risk. By this time, he was operating three thriving establishments built on a decade-long dominance of the juvenile market and an eye for extraordinary talent. Evans issued 20,000 copies of Under the Window, and the initial run sold out before he could release the next 50,000. This triumph began their long, profitable association. Between 1879 and 1898, Evans printed 932,100 works illustrated by Greenaway.

Despite the acclaim accompanying the release of each new Kate Greenaway book, her friends were free with advice on how she could improve her work—mistaking the simplicity of her carefully crafted world for a failure to grasp the principles of academic art. When artist Henry Stacy Marks told her to remove the dark shadows under the heels of her characters, she obeyed. When poet Frederick Locker-Lampson suggested she vary their stoic expressions, she responded politely but changed nothing. When Britain’s leading art critic, John Ruskin, advised her to strip her “girlies” entirely, she did not. “Will you—” Ruskin cajoled. “(It’s all for your own good!)… draw her for me without her hat—and, without her shoes,—(because of the heels) and without her mittens, and without her—frock and its frill?”

Greenaway’s style was the result of a sophisticated, intentional effort to capture the illusive magic of childhood. She was neither naïve nor uninformed. Literature, and contemporary art provided continuing inspiration, and Greenaway was a frequent visitor to London’s museums and galleries. She regularly participated in the city’s cultural life exhibiting her work at the Dudley Gallery, the Royal Academy, the Royal Institute of Painters in Watercolor, and the 1889 International Exhibition in Paris. Her first solo exhibition yielded sales of more than £1,000 and some distinguished patrons—among them painter Sir Frederic Leighton who purchased two of her watercolors.

Refined manners and a cautious reserve disguised Greenaway’s thorough understanding of the worth

|

| Art from Kate's last book |

The Kate Greenaway Medal was established by The Library Association of the United Kingdom in 1955 for distinguished illustration in a book for children. The award is given annually in the United Kingdom by CILIP, the Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals. You can look at a list of the winners of this prestigious award here. Titles that I have loved that won the award include The Lost Words by Jack Morris, This Is Not My Hat by Jon Klassen, Ella's Big Chance by Shirley Hughes, and Mrs. Cockle’s Cat by Antony Maitland.

.jpg)